Adner, R., & Helfat, C. E. (2003). Corporate effects and dynamic managerial capabilities. Strategic management journal, 24(10), 1011-1025. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smj.331

Bertua, C., Anderson, N., & Salgado, J. F. (2005). The predictive validity of cognitive ability tests: A UK meta?analysis. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 78(3), 387-409. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317905X26994

Coll, R. K., & Zegwaard, K. E. (2006). Perceptions of desirable graduate competencies for science and technology new graduates. Research in Science & Technological Education, 24(1), 29-58. https://doi.org/10.1080/02635140500485340

Durán, W. F., & Aguado, D. (2022). CEOs’ managerial cognition and dynamic capabilities: a meta-analytical study from the microfoundations approach. Journal of Management & Organization, 28(3), 451-479. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2022.24

Fleming, J., Martin, A. J., Hughes, H., & Zinn, C. (2009). Maximizing work-integrated learning experiences through identifying graduate competencies for employability: A case study of sport studies in higher education. International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning, 10(3), 189.

Helfat, C. E., & Peteraf, M. A. (2015). Managerial cognitive capabilities and the microfoundations of dynamic capabilities. Strategic management journal, 36(6), 831-850. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2247

Pang, E., Wong, M., Leung, C. H., & Coombes, J. (2019). Competencies for fresh graduates’ success at work: Perspectives of employers. Industry and Higher Education, 33(1), 55-65. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950422218792333

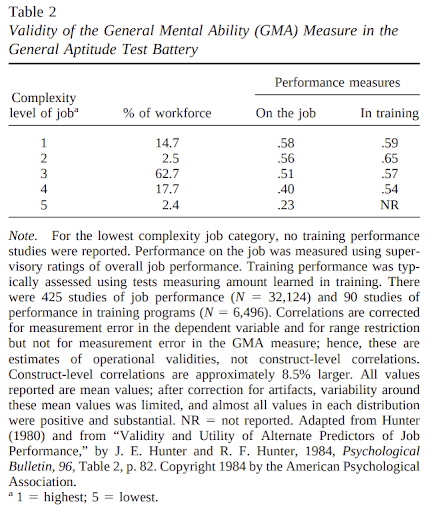

Salgado, J. F., & Moscoso, S. (2019). Meta-analysis of the validity of general mental ability for five performance criteria: Hunter and Hunter (1984) revisited. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2227. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02227

Schmidt, F. L., & Hunter, J. (2004). General mental ability in the world of work: occupational attainment and job performance. Journal of personality and social psychology, 86(1), 162. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.86.1.162

Wilk, S. L., & Sackett, P. R. (1996). Longitudinal analysis of ability?job complexity fit and job change. Personnel psychology, 49(4), 937-967. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1996.tb02455.x

Inloggen

Inloggen

Registreren

Registreren

Comments (0)

No reviews found

Add Comment