Artikel

16

januari

What Happens When an Amateur Cyclist Rides the Entire Tour de France Route

The 2000s-era reality show Pros vs. Joes was a great concept, but it didn’t give recreational endurance athletes much to fantasize about. Getting struck out by Darryl Strawberry or dunked on by Dennis Rodman is one thing, but how about trying to reel in a breakaway by Jonas Vingegaard after cycling hundreds of miles?

That’s not quite what a new paper in the Journal of Applied Physiology offers, but it’s the closest scientific equivalent. Researchers from Spain and the United States, led by David Barranco-Gil, Xabier Muriel, and Pedro Valenzuela, present a head-to-head matchup of the physiological data from two cyclists who completed last year’s Tour de France. One was a 27-year-old all-arounder who competed in the actual race for one of the World Tour teams. The other was a 58-year-old, 212-pound amateur who rode the entire Tour de France route starting a week before the race, as part of a fund-raising event for leukemia.

The results weren’t close. The pro covered 2,116 miles with 170,000 feet of elevation gain in 21 stages in a cumulative total of 87 hours; the Joe covered it in 191 hours, of which 158 were spent actually cycling. But the data is nonetheless interesting for what it tells us about the unexpectedly high limits of sustained endurance in (as the researchers put it) “mortals.” With apologies to Samuel Johnson, a 58-year-old amateur completing the Tour de France is like a dog walking on its hind legs: it’s not that it’s done well, but you’re surprised to see it done at all.

To be clear, the amateur didn’t just roll off the couch and decide to do the Tour de France one morning. He started training for the event a year and a half in advance, and reported doing 10 to 15 hours of cycling a week for the year leading up to it, and 15 to 20 hours a week for the last four months. In comparison, the pro was doing 18 to 22 hours a week for those last four months, which isn’t that much more—although the pro was covering 400 miles a week, double what the amateur was doing.

Based on power meter data from training, the pro had an estimated VO2 max of 80.5 ml/kg/min, while the amateur was at 45.4 ml/kg/min. For reference, a value of 43.4 would put him at the 90th percentile for men in their fifties, though it would be right around the median for a man in his twenties. Their functional threshold powers, a measure of the threshold between sustainable and unsustainable outputs, were 375 watts and 286 watts.

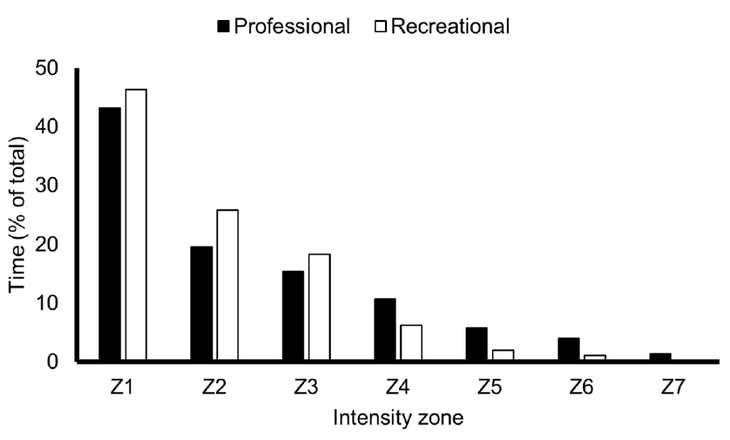

These measures of fitness are important because they allow us to make an apples-to-apples comparison of how hard the riders were pushing. The amateur was slower, but was he pushing just as hard relative to his fitness? Not quite—which isn’t surprising, since the pro was racing for his livelihood while the amateur was on vacation, and also since the amateur was spending twice as long on his bike each day. Here’s the distribution of relative time spent in seven different intensity zones:

The differences aren’t enormous, but it’s clear that the amateur spent more time in the lower three zones, while the pro spent more time in the upper four zones.

The most significant piece of data, though, is one of the simplest. Over the course of the three-week event, the pro’s weight stayed stable, while the amateur lost just two or three pounds. This is despite the fact that the pro was burning an estimated 7,098 calories per day (based on his power data and estimates of basal and non-exercise metabolism derived from his body size), while the amateur was burning 8,580 calories per day. The difference is mostly because the amateur was bigger: 6’3”, 212 pounds compared to 5’11”, 148 pounds.

Back in 2019, I wrote about some fascinating research on what scientists dubbed “sustained maximal human energy expenditure” (and what journalists were calling the “ultimate limit of human endurance”). The basic idea was that, in the long term, our ability to sustain high levels of activity is fundamentally limited by our ability to consume, digest, and metabolize sufficient calories to fuel that activity. You can burn a stupid amount of calories doing a 24-hour race (close to 10,000, by one estimate), but you can’t do that day after day, because you’re operating at a deficit, burning calories that you’ve previously stored as fat.

When Herman Pontzer, John Speakman, and other researchers plotted calorie burn versus duration, they found that the curve flattened out at a calorie-burning rate of around 2.5 times your basal metabolic rate. You can burn more for short periods of time, but the clock is ticking because you can’t replace those calories. This “alimentary limit” on how many calories we can take in, the researchers proposed, is what ultimately defines our maximum sustained endurance.

There were a few scraps of data that didn’t seem to fit with this hypothesis, most notably from Tour de France cyclists who reportedly burned more than 3.5 times their basal metabolic rate for weeks at a time without losing appreciable weight. Was this because modern sports nutrition, with its easily digestible drinks and gels, enables endurance athletes to push beyond the normal limits of digestion? Or because elite cyclists are digestive freaks of nature? It’s fair to say that the normal limit of human height is around seven feet, for example, but some people do grow taller. Maybe Tour de France cyclists are the Shawn Bradleys of digestion.

The new data, though limited by a sample size of just one in each group, suggests that pros aren’t the only ones who can break the proposed alimentary limit. The pro burned about 3.8 times his basal metabolic rate; the amateur hit 4.3, largely because he spent so much more time in the saddle and less time in bed. And they both did it without losing appreciable weight. Eating and digesting, in other words, is one event where the Joes really can compete with the pros.

For more Sweat Science, join me on Threads and Facebook, sign up for the email newsletter, and check out my book Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance.

What's your reaction ?

Follow us on Social Media

Some Categories

Recent posts

July 27, 2024

Nieuwe kabinetsvisie: samen sterker tegen cyberdreigingen

July 24, 2024

Navigating AI Implementation: Try these strategies to overcome resistance.

July 24, 2024

Sick Leave Policy Netherlands Guidance for HR and Entrepreneur.

July 24, 2024

CSRD Reporting: Mandatory Reporting on Corporate Sustainability.

July 24, 2024

Training Budget: Investing in Employee Development.

Inloggen

Inloggen

Registreren

Registreren

Comments (0)

No reviews found

Add Comment